Medicine

Medicine is the science and art (ars medicina) of healing humans. It includes a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness. Before scientific medicine, healing arts were practiced along with alchemical and ritual practices that developed out of religious and cultural traditions. The term "Western medicine" was until recently used to refer to scientific and science-based practices to distinguish it from "Eastern medicine" — which are typically based in traditional, story-told, or otherwise non-scientific practices.

Contemporary medicine applies health science, biomedical research, and medical technology to diagnose and treat injury and disease, typically through medication, surgery, or some other form of therapy. The word medicine is derived from the Latin ars medicina, meaning the art of healing.[1][2]

Though medical technology and clinical expertise are pivotal to contemporary medicine, successful face-to-face relief of actual suffering continues to require the application of ordinary human feeling and compassion, known in English as bedside manner.[3]

Contents |

History

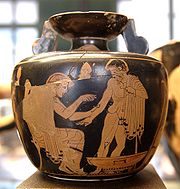

Prehistoric medicine incorporated plants (herbalism), animal parts and minerals. In many cases these materials were used ritually as magical substances by priests, shamans, or medicine men. Well-known spiritual systems include animism (the notion of inanimate objects having spirits), spiritualism (an appeal to gods or communion with ancestor spirits); shamanism (the vesting of an individual with mystic powers); and divination (magically obtaining the truth). The field of medical anthropology examines the ways in which culture and society are organized around or impacted by issues of health, health care and related issues.

Early records on medicine have been discovered from ancient Egyptian medicine, Babylonian medicine, Ayurvedic medicine (in the Indian subcontinent), classical Chinese medicine (predecessor to the modern traditional Chinese Medicine), and ancient Greek medicine and Roman medicine. The Egyptian Imhotep (3rd millennium BC) is the first physician in history known by name. Earliest records of dedicated hospitals come from Mihintale in Sri Lanka where evidence of dedicated medicinal treatment facilities for patients are found.[4][5] The Indian surgeon Sushruta described numerous surgical operations, including the earliest forms of plastic surgery.[6][7]

The Greek physician Hippocrates, considered the "father of medicine",[9][10] laid the foundation for a rational approach to medicine. Hippocrates introduced the Hippocratic Oath for physicians, which is still relevant and in use today, and was the first to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence".[11][12] The Greek physician Galen was also one of the greatest surgeons of the ancient world and performed many audacious operations, including brain and eye surgeries. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the onset of the Dark Ages, the Greek tradition of medicine went into decline in Western Europe, although it continued uninterrupted in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

After 750 CE, the Muslim Arab world had the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Sushruta translated into Arabic, and Islamic physicians engaged in some significant medical research. Notable Islamic medical pioneers include the polymath, Avicenna, who, along with Imhotep and Hippocrates, has also been called the "father of medicine".[13][14] He wrote The Canon of Medicine, considered one of the most famous books in the history of medicine.[15] Others include Abulcasis,[16] Avenzoar,[17] Ibn al-Nafis,[18] and Averroes.[19] Rhazes [20] was one of first to question the Greek theory of humorism, which nevertheless remained influential in both medieval Western and medieval Islamic medicine.[21] The Islamic Bimaristan hospitals were an early example of public hospitals.[22][23] However, the fourteenth and fifteenth century Black Death was just as devastating to the Middle East as to Europe, and it has even been argued that Western Europe was generally more effective in recovering from the pandemic than the Middle East.[24] In the early modern period, important early figures in medicine and anatomy emerged in Europe, including Gabriele Falloppio and William Harvey.

The major shift in medical thinking was the gradual rejection, especially during the Black Death in the 14th and 15th centuries, of what may be called the 'traditional authority' approach to science and medicine. This was the notion that because some prominent person in the past said something must be so, then that was the way it was, and anything one observed to the contrary was an anomaly (which was paralleled by a similar shift in European society in general - see Copernicus's rejection of Ptolemy's theories on astronomy). Physicians like Ibn al-Nafis and Vesalius improved upon or disproved some of the theories from the past.

Modern scientific biomedical research (where results are testable and reproducible) began to replace early Western traditions based on herbalism, the Greek "four humours" and other such pre-modern notions. The modern era really began with Edward Jenner's discovery of the smallpox vaccine at the end of the 18th century (inspired by the method of inoculation earlier practiced in Asia), Robert Koch's discoveries around 1880 of the transmission of disease by bacteria, and then the discovery of antibiotics around 1900. The post-18th century modernity period brought more groundbreaking researchers from Europe. From Germany and Austrian doctors (such as Rudolf Virchow, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Karl Landsteiner, and Otto Loewi) made contributions. In the United Kingdom Alexander Fleming, Joseph Lister, Francis Crick, and Florence Nightingale are considered important. From New Zealand and Australia came Maurice Wilkins, Howard Florey, and Frank Macfarlane Burnet). In the United States William Williams Keen, Harvey Cushing, William Coley, James D. Watson, Italy (Salvador Luria), Switzerland (Alexandre Yersin), Japan (Kitasato Shibasaburo), and France (Jean-Martin Charcot, Claude Bernard, Paul Broca and others did significant work). Russian Nikolai Korotkov also did significant work, as did Sir William Osler and Harvey Cushing.

As science and technology developed, medicine became more reliant upon medications. Throughout history and in Europe right until the late 18th century not only animal and plant products were used as medicine, but also human body parts and fluids.[25] Pharmacology developed from herbalism and many drugs are still derived from plants (atropine, ephedrine, warfarin, aspirin, digoxin, vinca alkaloids, taxol, hyoscine, etc.). The first of these was arsphenamine / Salvarsan discovered by Paul Ehrlich in 1908 after he observed that bacteria took up toxic dyes that human cells did not. Vaccines were discovered by Edward Jenner and Louis Pasteur. The first major class of antibiotics was the sulfa drugs, derived by French chemists originally from azo dyes. This has become increasingly sophisticated; modern biotechnology allows drugs targeted towards specific physiological processes to be developed, sometimes designed for compatibility with the body to reduce side-effects. Genomics and knowledge of human genetics is having some influence on medicine, as the causative genes of most monogenic genetic disorders have now been identified, and the development of techniques in molecular biology and genetics are influencing medical technology, practice and decision-making.

Evidence-based medicine is a contemporary movement to establish the most effective algorithms of practice (ways of doing things) through the use of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The movement is facilitated by modern global information science, which allows as much of the available evidence as possible to be collected and analyzed according to standard protocols which are then disseminated to healthcare providers. One problem with this 'best practice' approach is that it could be seen to stifle novel approaches to treatment. The Cochrane Collaboration leads this movement. A 2001 review of 160 Cochrane systematic reviews revealed that, according to two readers, 21.3% of the reviews concluded insufficient evidence, 20% concluded evidence of no effect, and 22.5% concluded positive effect.[26]

Clinical practice

In clinical practice doctors personally assess patients in order to diagnose, treat, and prevent disease using clinical judgment. The doctor-patient relationship typically begins an interaction with an examination of the patient's medical history and medical record, followed a medical interview[27] and a physical examination. Basic diagnostic medical devices (e.g. stethoscope, tongue depressor) are typically used. After examination for signs and interviewing for symptoms, the doctor may order medical tests (e.g. blood tests), take a biopsy, or prescribe pharmaceutical drugs or other therapies. Differential diagnosis methods help to rule out conditions based on the information provided. During the encounter, properly informing the patient of all relevant facts is an important part of the relationship and the development of trust. The medical encounter is then documented in the medical record, which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.[28] Followups may be shorter but follow the same general procedure.

The components of the medical interview[27] and encounter are:

- Chief complaint (cc): the reason for the current medical visit. These are the 'symptoms.' They are in the patient's own words and are recorded along with the duration of each one. Also called 'presenting complaint.'

- History of present illness / complaint (HPI): the chronological order of events of symptoms and further clarification of each symptom.

- Current activity: occupation, hobbies, what the patient actually does.

- Medications (Rx): what drugs the patient takes including prescribed, over-the-counter, and home remedies, as well as alternative and herbal medicines/herbal remedies. Allergies are also recorded.

- Past medical history (PMH/PMHx): concurrent medical problems, past hospitalizations and operations, injuries, past infectious diseases and/or vaccinations, history of known allergies.

- Social history (SH): birthplace, residences, marital history, social and economic status, habits (including diet, medications, tobacco, alcohol).

- Family history (FH): listing of diseases in the family that may impact the patient. A family tree is sometimes used.

- Review of systems (ROS) or systems inquiry: a set of additional questions to ask which may be missed on HPI: a general enquiry (have you noticed any weight loss, change in sleep quality, fevers, lumps and bumps? etc.), followed by questions on the body's main organ systems (heart, lungs, digestive tract, urinary tract, etc.).

The physical examination is the examination of the patient looking for signs of disease ('Symptoms' are what the patient volunteers, 'Signs' are what the healthcare provider detects by examination). The healthcare provider uses the senses of sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (e.g. in infection, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis). Taste has been made redundant by the availability of modern lab tests. Four actions are taught as the basis of physical examination: inspection, palpation (feel), percussion (tap to determine resonance characteristics), and auscultation (listen). This order may be modified depending on the main focus of the examination (e.g. a joint may be examined by simply "look, feel, move". Having this set order is an educational tool that encourages the practitioner to be systematic in their approach and refrain from using tools such as the stethoscope before they have fully evaluated the other modalities.

The clinical examination involves study of:

- Vital signs including height, weight, body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, hemoglobin oxygen saturation

- General appearance of the patient and specific indicators of disease (nutritional status, presence of jaundice, pallor or clubbing)

- Skin

- Head, eye, ear, nose, and throat (HEENT)

- Cardiovascular (heart and blood vessels)

- Respiratory (large airways and lungs)

- Abdomen and rectum

- Genitalia (and pregnancy if the patient is or could be pregnant)

- Musculoskeletal (including spine and extremities)

- Neurological (consciousness, awareness, brain, vision, cranial nerves, spinal cord and peripheral nerves)

- Psychiatric (orientation, mental state, evidence of abnormal perception or thought).

It is likely to be focussed on areas of interest highlighted in the medical history and may not include everything listed above.

Laboratory and imaging studies results may be obtained, if necessary.

The medical decision-making (MDM) process involves analysis and synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem.

The treatment plan may include ordering additional laboratory tests and studies, starting therapy, referral to a specialist, or watchful observation. Follow-up may be advised.

This process is used by primary care providers as well as specialists. It may take only a few minutes if the problem is simple and straightforward. On the other hand, it may take weeks in a patient who has been hospitalized with bizarre symptoms or multi-system problems, with involvement by several specialists.

On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical findings, and lab or imaging results or specialist consultations.

Institutions

Contemporary medicine is in general conducted within health care systems. Legal, credentialing and financing frameworks are established by individual governments, augmented on occasion by international organizations. The characteristics of any given health care system have significant impact on the way medical care is provided.

Advanced industrial countries (with the exception of the United States) [29][30] and many developing countries provide medical services through a system of universal health care which aims to guarantee care for all through a single-payer health care system, or compulsory private or co-operative health insurance. This is intended to ensure that the entire population has access to medical care on the basis of need rather than ability to pay. Delivery may be via private medical practices or by state-owned hospitals and clinics, or by charities; most commonly by a combination of all three.

Most tribal societies, but also some communist countries (e.g. China) and the United States,[29][30] provide no guarantee of health care for the population as a whole. In such societies, health care is available to those that can afford to pay for it or have self insured it (either directly or as part of an employment contract) or who may be covered by care financed by the government or tribe directly.

Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality and pricing greatly affects the choice by patients / consumers and therefore the incentives of medical professionals. While the US health care system has come under fire for lack of openness,[31] new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of information for commercial gain on the other.

Delivery

Provision of medical care is classified into primary, secondary and tertiary care categories.

Primary care medical services are provided by physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or other health professionals who have first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care. These occur in physician offices, clinics, nursing homes, schools, home visits and other places close to patients. About 90% of medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses, preventive care and health education for all ages and both sexes.

Secondary care medical services are provided by medical specialists in their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or treated the patient. Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include both ambulatory care and inpatient services, emergency rooms, intensive care medicine, surgery services, physical therapy, labor and delivery, endoscopy units, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services, hospice centers, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting.

Tertiary care medical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally available at local hospitals. These include trauma centers, burn treatment centers, advanced neonatology unit services, organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy, radiation oncology, etc.

Modern medical care also depends on information - still delivered in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly nowadays by electronic means.

Branches

Working together as an interdisciplinary team, many highly trained health professionals besides medical practitioners are involved in the delivery of modern health care. Examples include: nurses, emergency medical technicians and paramedics, laboratory scientists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, respiratory therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, radiographers, dietitians and bioengineers.

The scope and sciences underpinning human medicine overlap many other fields. Dentistry, while a separate discipline from medicine, is considered a medical field.

A patient admitted to hospital is usually under the care of a specific team based on their main presenting problem, e.g. the Cardiology team, who then may interact with other specialties, e.g. surgical, radiology, to help diagnose or treat the main problem or any subsequent complications / developments.

Physicians have many specializations and subspecializations into certain branches of medicine, which are listed below. There are variations from country to country regarding which specialties certain subspecialties are in.

The main branches of medicine used in Wikipedia are:

- Basic sciences of medicine; this is what every physician is educated in, and some return to in biomedical research.

- Medical specialties

- Interdisciplinary fields, where different medical specialties are mixed to function in certain occasions.

Basic sciences

- Anatomy is the study of the physical structure of organisms. In contrast to macroscopic or gross anatomy, cytology and histology are concerned with microscopic structures.

- Biochemistry is the study of the chemistry taking place in living organisms, especially the structure and function of their chemical components.

- Biomechanics is the study of the structure and function of biological systems by means of the methods of Mechanics.

- Biostatistics is the application of statistics to biological fields in the broadest sense. A knowledge of biostatistics is essential in the planning, evaluation, and interpretation of medical research. It is also fundamental to epidemiology and evidence-based medicine.

- Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that uses the methods of physics and physical chemistry to study biological systems.

- Cytology is the microscopic study of individual cells.

- Embryology is the study of the early development of organisms.

- Epidemiology is the study of the demographics of disease processes, and includes, but is not limited to, the study of epidemics.

- Genetics is the study of genes, and their role in biological inheritance.

- Histology is the study of the structures of biological tissues by light microscopy, electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

- Immunology is the study of the immune system, which includes the innate and adaptive immune system in humans, for example.

- Medical physics is the study of the applications of physics principles in medicine.

- Microbiology is the study of microorganisms, including protozoa, bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

- Molecular biology is the study of molecular underpinnings of the process of replication, transcription and translation of the genetic material.

- Neuroscience includes those disciplines of science that are related to the study of the nervous system. A main focus of neuroscience is the biology and physiology of the human brain and spinal cord.

- Nutrition science (theoretical focus) and dietetics (practical focus) is the study of the relationship of food and drink to health and disease, especially in determining an optimal diet. Medical nutrition therapy is done by dietitians and is prescribed for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, weight and eating disorders, allergies, malnutrition, and neoplastic diseases.

- Pathology as a science is the study of disease—the causes, course, progression and resolution thereof.

- Pharmacology is the study of drugs and their actions.

- Photobiology is the study of the interactions between non-ionizing radiation and living organisms.

- Physiology is the study of the normal functioning of the body and the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

- Radiobiology is the study of the interactions between ionizing radiation and living organisms.

- Toxicology is the study of hazardous effects of drugs and poisons.

Specialties

In the broadest meaning of "medicine", there are many different specialties. In the UK most specialities will have their own body or college (collectively known as the Royal Colleges, although currently not all use the term "Royal") which have their own entrance exam. The development of a speciality is often driven by new technology (such as the development of effective anaesthetics) or ways of working (e.g. emergency departments) which leads to the desire to form a unifying body of doctors and thence the prestige of administering their own exam.

Within medical circles, specialities usually fit into one of two broad categories: "Medicine" and "Surgery." "Medicine" refers to the practice of non-operative medicine, and most subspecialties in this area require preliminary training in "Internal Medicine". In the UK this would traditionally have been evidenced by obtaining the MRCP (An exam allowing Membership of the Royal College of Physicians or the equivalent college in Scotland or Ireland). "Surgery" refers to the practice of operative medicine, and most subspecialties in this area require preliminary training in "General Surgery." (In the UK: Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (MRCS).)There are some specialties of medicine that at the present time do not fit easily into either of these categories, such as radiology, pathology, or anesthesia. Most of these have branched from one or other of the two camps above - for example anaesthesia developed first as a faculty of the Royal College of Surgeons (for which MRCS/FRCS would have been required) before becoming the Royal College of Anaesthetists and membership of the college is by sitting the FRCA (Fellowship of the Royal College of Anesthetists).

Surgery

Surgical specialties employ operative treatment. In addition, surgeons must decide when an operation is necessary, and also treat many non-surgical issues, particularly in the surgical intensive care unit (SICU), where a variety of critical issues arise. Surgery has many subspecialties, e.g. general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, colorectal surgery, neurosurgery, maxillofacial surgery, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, oncologic surgery, transplant surgery, trauma surgery, urology, vascular surgery, and pediatric surgery. In some centers, anesthesiology is part of the division of surgery (for historical and logistical reasons), although it is not a surgical discipline.

Surgical training in the U.S. requires a minimum of five years of residency after medical school. Sub-specialties of surgery often require seven or more years. In addition, fellowships can last an additional one to three years. Because post-residency fellowships can be competitive, many trainees devote two additional years to research. Thus in some cases surgical training will not finish until more than a decade after medical school. Furthermore, surgical training can be very difficult and time consuming.

'Medicine' as a specialty

Internal medicine is the medical specialty concerned with the diagnosis, management and nonsurgical treatment of unusual or serious diseases, either of one particular organ system or of the body as a whole. According to some sources, an emphasis on internal structures is implied.[32] In North America, specialists in internal medicine are commonly called "internists". Elsewhere, especially in Commonwealth nations, such specialists are often called physicians.[33] These terms, internist or physician (in the narrow sense, common outside North America), generally exclude practitioners of gynecology and obstetrics, pathology, psychiatry, and especially surgery and its subspecialities.

Because their patients are often seriously ill or require complex investigations, internists do much of their work in hospitals. Formerly, many internists were not subspecialized; such general physicians would see any complex nonsurgical problem; this style of practice has become much less common. In modern urban practice, most internists are subspecialists: that is, they generally limit their medical practice to problems of one organ system or to one particular area of medical knowledge. For example, gastroenterologists and nephrologists specialize respectively in diseases of the gut and the kidneys.[34]

In Commonwealth and some other countries, specialist pediatricians and geriatricians are also described as specialist physicians (or internists) who have subspecialized by age of patient rather than by organ system. Elsewhere, especially in North America, general pediatrics is often a form of Primary care.

There are many subspecialities (or subdisciplines) of internal medicine:

-

- Cardiology

- Critical care medicine

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatrics

- Haematology

- Hepatology

- Infectious diseases

- Nephrology

- Oncology

- Pediatrics

- Pulmonology/Pneumology/Respirology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep medicine

Training in internal medicine (as opposed to surgical training), varies considerably across the world: see the articles on Medical education and Physician for more details. In North America, it requires at least three years of residency training after medical school, which can then be followed by a one to three year fellowship in the subspecialties listed above. In general, resident work hours in medicine are less than those in surgery, averaging about 60 hours per week in the USA. This difference does not apply in the UK where all doctors are now required by law to work less than 48 hours per week on average.

Diagnostic specialties

- Clinical laboratory sciences are the clinical diagnostic services which apply laboratory techniques to diagnosis and management of patients. In the United States these services are supervised by a pathologist. The personnel that work in these medical laboratory departments are technically trained staff who do not hold medical degrees, but who usually hold an undergraduate medical technology degree, who actually perform the tests, assays, and procedures needed for providing the specific services. Subspecialties include Transfusion medicine, Cellular pathology, Clinical chemistry, Hematology, Clinical microbiology and Clinical immunology.

- Pathology as a medical specialty is the branch of medicine that deals with the study of diseases and the morphologic, physiologic changes produced by them. As a diagnostic specialty, pathology can be considered the basis of modern scientific medical knowledge and plays a large role in evidence-based medicine. Many modern molecular tests such as flow cytometry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, gene rearrangements studies and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) fall within the territory of pathology.

- Radiology is concerned with imaging of the human body, e.g. by x-rays, x-ray computed tomography, ultrasonography, and nuclear magnetic resonance tomography.

- Nuclear medicine is concerned with studying human organ systems by administering radiolabelled substances (radiopharmaceuticals) to the body, which can then be imaged outside the body by a gamma camera or a PET scanner. Each radiopharmaceutical consists of two parts: a tracer which is specific for the function under study (e.g., neurotransmitter pathway, metabolic pathway, blood flow, or other), and a radionuclide (usually either a gamma-emitter, or a positron emitter). There is a degree of overlap between nuclear medicine and radiology, as evidenced by the emergence of combined devices such as the PET/CT scanner.

- Clinical neurophysiology is concerned with testing the physiology or function of the central and peripheral aspects of the nervous system. These kinds of tests can be divided into recordings of: (1) spontaneous or continuously running electrical activity, or (2) stimulus evoked responses. Subspecialties include Electroencephalography, Electromyography, Evoked potential, Nerve conduction study and Polysomnography. Sometimes these tests are performed by techs without a medical degree, but the interpretation of these tests is done by a medical professional.

Other major specialties

The followings are some major medical specialties that do not directly fit into any of the above mentioned groups.

- Dermatology is concerned with the skin and its diseases. In the UK, dermatology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Emergency medicine is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of acute or life-threatening conditions, including trauma, surgical, medical, pediatric, and psychiatric emergencies.

- Family medicine, family practice, general practice or primary care is, in many countries, the first port-of-call for patients with non-emergency medical problems.

- Obstetrics and gynecology (often abbreviated as OB/GYN (American English) or Obs & Gynae (British English)) are concerned respectively with childbirth and the female reproductive and associated organs. Reproductive medicine and fertility medicine are generally practiced by gynecological specialists.

- Medical Genetics is concerned with the diagnosis and management of hereditary disorders.

- Neurology is concerned with diseases of the nervous system. In the UK, neurology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Ophthalmology exclusively concerned with the eye and ocular adnexa, combining conservative and surgical therapy.

- Pediatrics (AE) or paediatrics (BE) is devoted to the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Like internal medicine, there are many pediatric subspecialties for specific age ranges, organ systems, disease classes, and sites of care delivery.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation (or physiatry) is concerned with functional improvement after injury, illness, or congenital disorders.

- Psychiatry is the branch of medicine concerned with the bio-psycho-social study of the etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cognitive, perceptual, emotional and behavioral disorders. Related non-medical fields include psychotherapy and clinical psychology.

- Preventive medicine is the branch of medicine concerned with preventing disease.

- Community health or public health is an aspect of health services concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis.

- Occupational medicine's principal role is the provision of health advice to organizations and individuals to ensure that the highest standards of health and safety at work can be achieved and maintained.

- Aerospace medicine deals with medical problems related to flying and space travel.

Interdisciplinary fields

Some interdisciplinary sub-specialties of medicine include:

- Addiction medicine deals with the treatment of addiction.

- Bioethics is a field of study which concerns the relationship between biology, science, medicine and ethics, philosophy and theology.

- Biomedical Engineering is a field dealing with the application of engineering principles to medical practice.

- Clinical pharmacology is concerned with how systems of therapeutics interact with patients.

- Conservation medicine studies the relationship between human and animal health, and environmental conditions. Also known as ecological medicine, environmental medicine, or medical geology.

- Disaster medicine deals with medical aspects of emergency preparedness, disaster mitigation and management.

- Diving medicine (or hyperbaric medicine) is the prevention and treatment of diving-related problems.

- Evolutionary medicine is a perspective on medicine derived through applying evolutionary theory.

- Forensic medicine deals with medical questions in legal context, such as determination of the time and cause of death.

- Gender-based medicine studies the biological and physiological differences between the human sexes and how that affects differences in disease.

- Hospital medicine is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Physicians whose primary professional focus is hospital medicine are called hospitalists in the USA.

- Laser medicine involves the use of lasers in the diagnostics and/or treatment of various conditions.

- Medical humanities includes the humanities (literature, philosophy, ethics, history and religion), social science (anthropology, cultural studies, psychology, sociology), and the arts (literature, theater, film, and visual arts) and their application to medical education and practice.

- Medical informatics, medical computer science, medical information and eHealth are relatively recent fields that deal with the application of computers and information technology to medicine.

- Nosology is the classification of diseases for various purposes.

- Nosokinetics is the science/subject of measuring and modelling the process of care in health and social care systems.

- Pain management (also called pain medicine, or algiatry) is the medical discipline concerned with the relief of pain.

- Palliative care is a relatively modern branch of clinical medicine that deals with pain and symptom relief and emotional support in patients with terminal illnesses including cancer and heart failure.

- Pharmacogenomics is a form of individualized medicine.

- Sexual medicine is concerned with diagnosing, assessing and treating all disorders related to sexuality.

- Sports medicine deals with the treatment and preventive care of athletes, amateur and professional. The team includes specialty physicians and surgeons, athletic trainers, physical therapists, coaches, other personnel, and, of course, the athlete.

- Therapeutics is the field, more commonly referenced in earlier periods of history, of the various remedies that can be used to treat disease and promote health [1].

- Travel medicine or emporiatrics deals with health problems of international travelers or travelers across highly different environments.

- Urgent care focuses on delivery of unscheduled, walk-in care outside of the hospital emergency department for injuries and illnesses that are not severe enough to require care in an emergency department. In some jurisdictions this function is combined with the emergency room.

- Veterinary medicine; veterinarians apply similar techniques as physicians to the care of animals.

- Wilderness medicine entails the practice of medicine in the wild, where conventional medical facilities may not be available.

- Many other health science fields, e.g. dietetics

Education

Medical education and training varies around the world. It typically involves entry level education at a university medical school, followed by a period of supervised practice or internship, and/or residency. This can be followed by postgraduate vocational training. A variety of teaching methods have been employed in medical education, still itself a focus of active research.

Many regulatory authorities require continuing medical education, since knowledge, techniques and medical technology continue to evolve at a rapid rate.

Legal controls

In most countries, it is a legal requirement for a medical doctor to be licensed or registered. In general, this entails a medical degree from a university and accreditation by a medical board or an equivalent national organization, which may ask the applicant to pass exams. This restricts the considerable legal authority of the medical profession to physicians that are trained and qualified by national standards. It is also intended as an assurance to patients and as a safeguard against charlatans that practice inadequate medicine for personal gain. While the laws generally require medical doctors to be trained in "evidence based", Western, or Hippocratic Medicine, they are not intended to discourage different paradigms of health.

Doctors who are negligent or intentionally harmful in their care of patients can face charges of medical malpractice and be subject to civil, criminal, or professional sanctions.

Controversy

The Catholic social theorist Ivan Illich subjected contemporary western medicine to detailed attack in his Medical Nemesis, first published in 1975. He argued that the medicalization in recent decades of so many of life's vicissitudes — birth and death, for example — frequently caused more harm than good and rendered many people in effect lifelong patients. He marshalled a body of statistics to show what he considered the shocking extent of post-operative side-effects and drug-induced illness in advanced industrial society. He was the first to introduce to a wider public the notion of iatrogenesis.[35] Others have since voiced similar views, but none so trenchantly, perhaps, as Illich.[36]

Through the course of the twentieth century, healthcare providers focused increasingly on the technology that was enabling them to make dramatic improvements in patients' health. The ensuing development of a more mechanistic, detached practice, with the perception of an attendant loss of patient-focused care, known as the medical model of health, led to criticisms that medicine was neglecting a holistic model. The inability of modern medicine to properly address some common complaints continues to prompt many people to seek support from alternative medicine. Although most alternative approaches lack scientific validation, some, notably acupuncture for some conditions and certain herbs, are backed by evidence.[37]

Medical errors and overmedication are also the focus of complaints and negative coverage. Practitioners of human factors engineering believe that there is much that medicine may usefully gain by emulating concepts in aviation safety, where it is recognized that it is dangerous to place too much responsibility on one "superhuman" individual and expect him or her not to make errors. Reporting systems and checking mechanisms are becoming more common in identifying sources of error and improving practice. Clinical versus statistical, algorithmic diagnostic methods were famously examined in psychiatric practice in a 1954 book by Paul E. Meehl, which controversially found statistical methods superior.[38] A 2000 meta-analysis comparing these methods in both psychology and medicine found that statistical or "mechanical" diagnostic methods were generally, although not always, superior.[38]

Disparities in quality of care given are often an additional cause of controversy.[39] For example, elderly mentally ill patients received poorer care during hospitalization in a 2008 study.[40] Rural poor African-American men were used in a study of syphilis that denied them basic medical care.

Honors and awards

The highest honor awarded in medicine is the Nobel Prize in Medicine, awarded since 1901 by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Outline of health

- List of causes of death by rate

- List of diseases

- List of disorders

- List of important publications in medicine

- Medical Encyclopedia

- Medical equipment

- Medical literature

- Medical sociology

- Pharmacognosy

- Timeline of medicine and medical technology

References

- ↑ Etymology: Latin: medicina, from ars medicina "the medical art," from medicus "physician."(Etym.Online) Cf. mederi "to heal," etym. "know the best course for," from PIE base *med- "to measure, limit. Cf. Greek medos "counsel, plan," Avestan vi-mad "physician")

- ↑ "Medicine" Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ Culliford Larry (December 2002). "Spirituality and clinical care (Editorial)". British Medical Journal 325 (7378): 1434–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1434. PMID 12493652.

- ↑ Prof. Arjuna Aluvihare, "Rohal Kramaya Lovata Dhayadha Kale Sri Lankikayo" Vidhusara Science Magazine, Nov. 1993.

- ↑ Resource Mobilization in Sri Lanka's Health Sector - Rannan-Eliya, Ravi P. & De Mel, Nishan, Harvard School of Public Health & Health Policy Programme, Institute of Policy Studies , February 1997, Page 19. Accessed 2008-02-22.

- ↑ A. Singh and D. Sarangi (2003). "We need to think and act", Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery.

- ↑ H. W. Longfellow (2002). "History of Plastic Surgery in India", Journal of Postgraduate Medicine.

- ↑ Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus., U.S. National Library of Medicine

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The father of modern medicine: the first research of the physical factor of tetanus, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

- ↑ Grammaticos P.C. & Diamantis A. (2008). "Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus". Hell J Nucl Med 11 (1): 2–4. PMID 18392218.

- ↑ Garrison 1966, p. 97

- ↑ Martí-Ibáñez 1961, p. 90

- ↑ Becka J (1980). "The father of medicine, Avicenna, in our science and culture: Abu Ali ibn Sina (980-1037) (Czech title: Otec lékarů Avicenna v nasí vĕdĕ a kulture)" (in Czech). Cas Lek Cesk 119 (1): 17–23. PMID 6989499.

- ↑ Medical Practitioners

- ↑ ""The Canon of Medicine" (work by Avicenna)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. http://www.britannica.com/eb/topic-92902/The-Canon-of-Medicine. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Ahmad, Z. (St Thomas' Hospital) (2007). "Al-Zahrawi - The Father of Surgery". ANZ Journal of Surgery 77 (Suppl. 1): A83. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04130_8.x

- ↑ Rabie E. Abdel-Halim (2006), "Contributions of Muhadhdhab Al-Deen Al-Baghdadi to the progress of medicine and urology", Saudi Medical Journal 27 (11): 1631-1641.

- ↑ Chairman's Reflections (2004), "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting", Heart Views 5 (2): 74-85 [80].

- ↑ Martín-Araguz A, Bustamante-Martínez C, Fernández-Armayor Ajo V, Moreno-Martínez JM (2002-05-01—15). "Neuroscience in al-Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine" (in Spanish). Revista de neurología 34 (9): 877–892. PMID 12134355.

- ↑ David W. Tschanz, PhD (2003), "Arab(?) Roots of European Medicine", Heart Views 4 (2).

- ↑ On the dominance of the Greek humoral theory, which was the basis for the practice of bloodletting, in medieval Islamic medicine see Peter E. Pormann and E. Savage Smith,Medieval Islamic medicine, Georgetown University, Washington DC, 2007 p. 10, 43-45.

- ↑ Micheau, Françoise. "The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East". pp. 991–2, in (Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp. 985–1007)

- ↑ Peter Barrett (2004), Science and Theology Since Copernicus: The Search for Understanding, p. 18, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 056708969X.

- ↑ Michael Dols has shown that the Black Death was much more commonly believed by European authorities than by Middle Eastern authorities to be contagious; as a result, flight was more commonly counseled, and in urban Italy quarantines were organized on a much wider level than in urban Egypt or Syria (The Black Death in the Middle East Princeton, 1977, p. 119; 285-290.

- ↑ Peter Cooper, "Medicinal properties of body parts", The Pharmaceutical Journal, 18/25 December 2004, Vol. 273 / No 7330, pp. 900-902 http://www.pharmj.com/editorial/20041218/christmas/p900bodyparts.html

- ↑ Ezzo J, Bausell B, Moerman DE, Berman B, Hadhazy V (2001). "Reviewing the reviews. How strong is the evidence? How clear are the conclusions?". Int J Technol Assess Health Care 17 (4): 457–466. PMID 11758290.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Coulehan JL, Block MR (2005). The Medical Interview: Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice (5th ed.). F. A. Davis. ISBN 0-8036-1246-X. OCLC 232304023.

- ↑ Addison K, Braden JH, Cupp JE, Emmert D, et al. (AHIMA e-HIM Work Group on the Legal Health Record) (September 2005). "Update: Guidelines for Defining the Legal Health Record for Disclosure Purposes". Journal of AHIMA 78 (8): 64A–G. PMID 16245584. http://library.ahima.org/xpedio/groups/public/documents/ahima/bok1_027921.hcsp?dDocName=bok1_027921.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations, Institute of Medicine at the National Academies of Science, 2004-01-14

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "The Case For Single Payer, Universal Health Care For The United States". Cthealth.server101.com. http://cthealth.server101.com/the_case_for_universal_health_care_in_the_united_states.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Martin Sipkoff (January 2004). "Transparency called key to uniting cost control, quality improvement". Managed Care. http://www.managedcaremag.com/archives/0401/0401.forum.html.

- ↑ internal medicine at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ H.W. Fowler. (1994). A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (Wordsworth Collection) (Wordsworth Collection). NTC/Contemporary Publishing Company. ISBN 1853263184.

- ↑ "The Royal Australasian College of Physicians: What are Physicians?". Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20080306053048/http://www.racp.edu.au/index.cfm?objectid=49EF1EB5-2A57-5487-D74DBAFBAE9143A3. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Illich Ivan (1974). Medical Nemesis. London: Calder & Boyars. ISBN 0714510963. OCLC 224760852.

- ↑ Postman Neil (1992). Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Knopf. OCLC 24694343.

- ↑ The HealthWatch Award 2005: Prof. Edzard Ernst, Complementary medicine: the good the bad and the ugly. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Grove WH, Zald DH, Lebow BS, Snitz BE, Nelson C. (2000). "Clinical versus mechanical prediction: A meta-analysis" (w). Psychological Assessment 12 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.19. PMID 10752360. http://www.psych.umn.edu/faculty/grove/096clinicalversusmechanicalprediction.pdf.

- ↑ "Eliminating Health Disparities". American Medical Association. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/public-health/eliminating-health-disparities.shtml.

- ↑ "Mental Disorders, Quality of Care, and Outcomes Among Older Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure". http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/65/12/1402.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||